-

Raymond Arnold

-

Kelly Austin

-

Les Blakebrough

-

Nicholas Blowers

-

Michaye Boulter

-

Pat Brassington

-

Lucinda Bresnehan

-

Irene Briant

-

Tim Burns

-

Jane Burton

-

Matt Coyle

-

Alex Davern

-

Amanda Davies

-

Michael Doolan

-

Britt Fazey

-

Julie Gough

-

Patrick Grieve

-

Neil Haddon

-

Rosie Hastie

-

Aunty Jeanette James

-

Locust Jones

-

David Keeling

-

Barbie Kjar

-

Ingo Kleinert

-

Annika Koops

-

Amber Koroluk-Stephenson

-

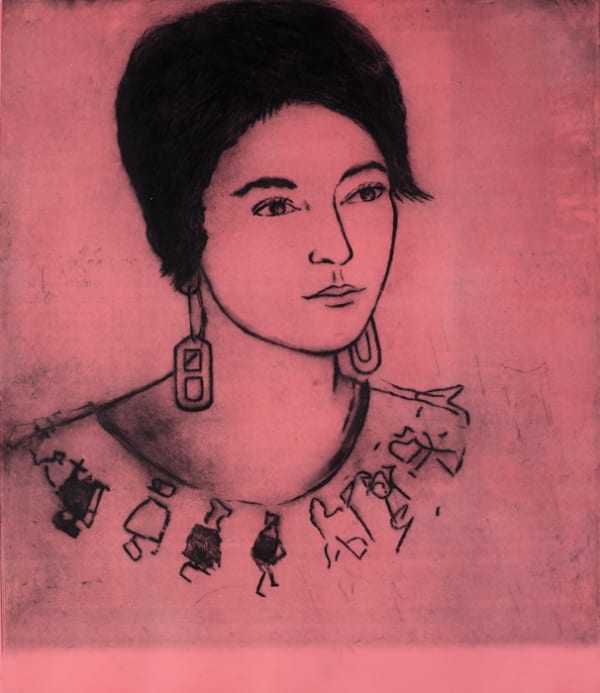

Dai Li

-

Sue Lovegrove

-

Anne MacDonald

-

Sara Maher

-

Nancy Mauro-Flude

-

Ricky Maynard

-

Mish Meijers

-

Ashlee Murray

-

Tom O'Hern

-

Nicole O'Loughlin

-

Alexander Okenyo

-

Brigita Ozolins

-

Robert O’Connor

-

Hermannsburg Potters

-

Caroline Rannersberger

-

Sally Rees

-

Joan Ross

-

Troy Ruffels

-

Michael Schlitz

-

Peter James Smith

-

Valerie Sparks

-

David Stephenson

-

Neridah Stockley

-

Stephanie Tabram

-

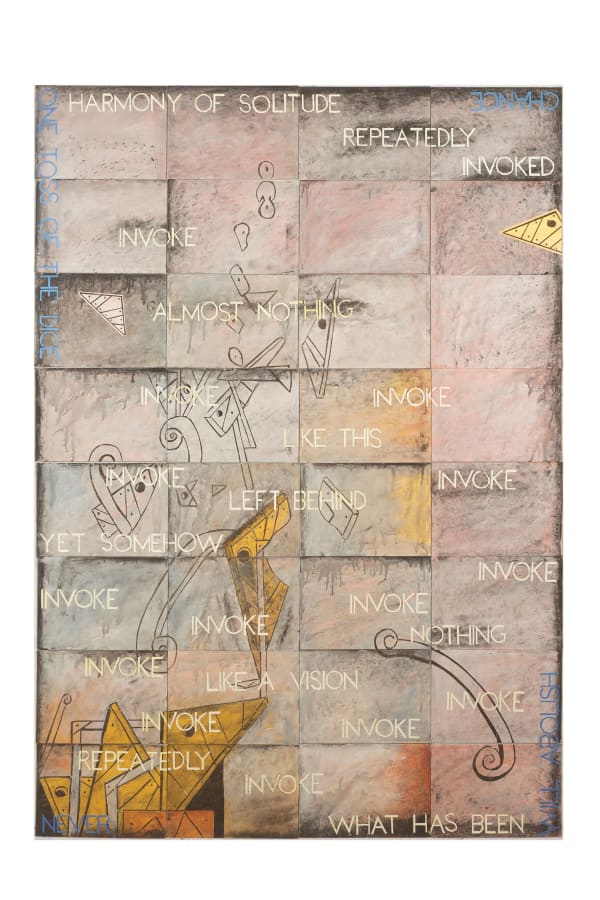

Imants Tillers

-

Lynne Uptin

-

Megan Walch

-

Nicola Gower Wallis

-

Richard Wastell

-

Belinda Winkler

-

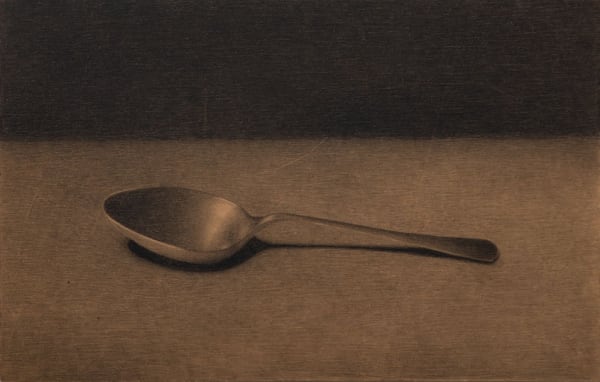

Philip Wolfhagen

-

Greg Wood

-

Bec Woolley

-

Helen Wright