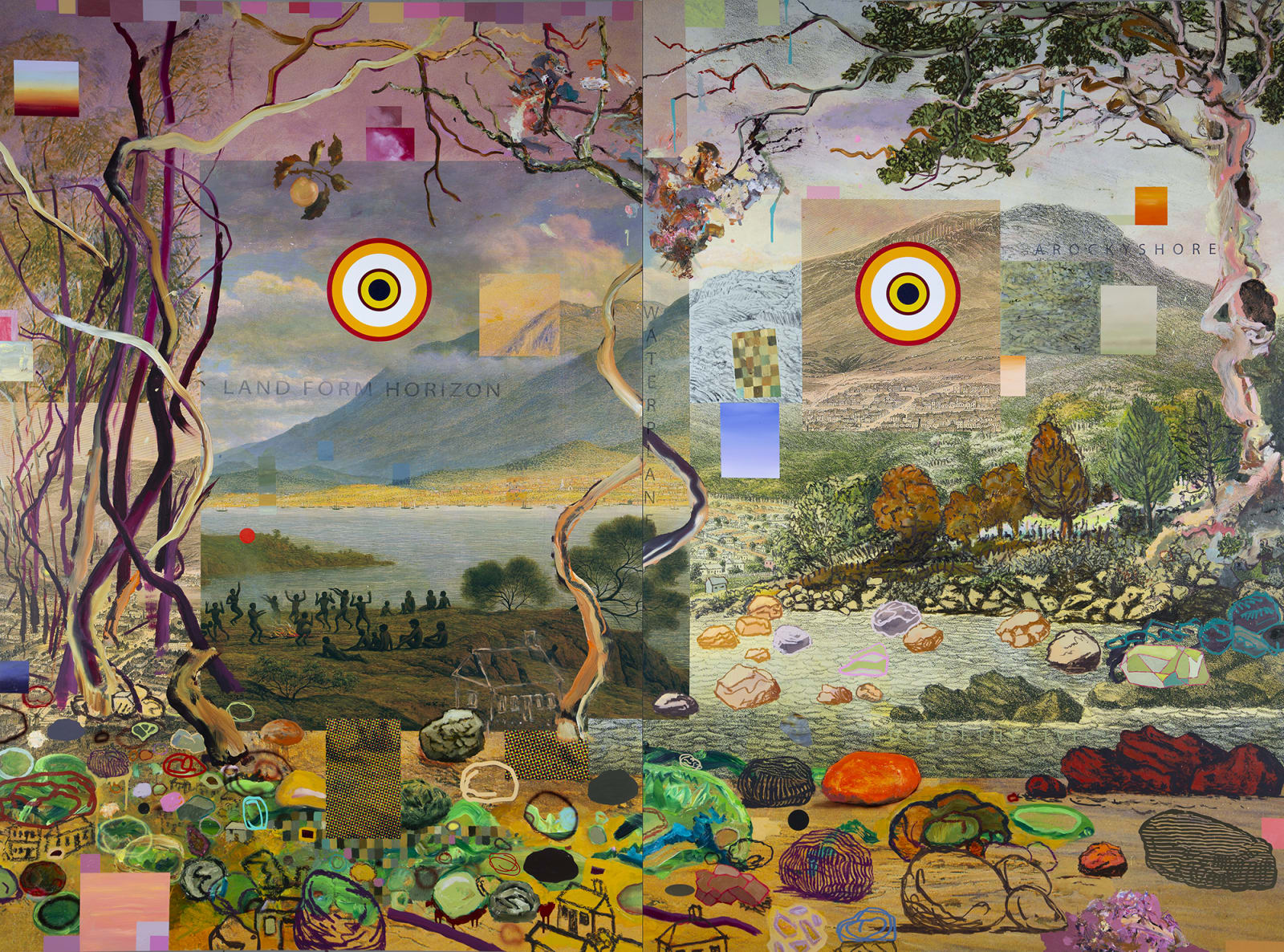

Neil Haddon and Leigh Woolley

We will bring our own views (and our own plans), 2018-2021

oil and digital print on aluminium panels

diptych: 180 x 240 cm (overall size)

BG7836

‘Re-viewing’ disappearing townscape Crucial to human existence, the freedom of outlook and outreach is embodied in island life. To ‘value a view’ is to acknowledge the intrinsic role of a...

‘Re-viewing’ disappearing townscape

Crucial to human existence, the freedom of outlook and outreach is embodied in island life.

To ‘value a view’ is to acknowledge the intrinsic role of a shared landscape. In response to a city’s location, the characteristics of its landform underpin, and progressively reveal; form, character and identity. All cities are experienced as landscapes, accordingly the way cities are experienced, where they are placed, not just how they are made, demand consideration, analysis and ‘re-view’.

Recognizing that townscape is ‘a word formed on the pattern of landscape’,1 the response engages the latent language of landscape, by grounding and locating disparate parts and layers in the moment of pastiched views. The intention is to offer a ‘frame of reference’ across scales, a ‘re-appearing’ of that which bounds identity in the dwelling region.

Waterplane and landform horizons sustain human presence, and in response, the sense of scale and proportion reinforces and reveals deep prospects, linking near and far, bounding location and urban identity. The margin between land and water confirms a continuous ‘civic’ edge. In being compelled to adapt the space of the city to the terrain, settlement is provided a meandering succession of movements – compelling orientation and re- orientation - revealing extensive and partial prospects and integrating land and its form into the settled world.

Spatially the regional dwelling experience contrasts ‘containment’ by high and rising ground, and ‘release’ across waterplanes. Reciprocally ‘landform horizons’ provide the undulating edge where force accumulates, while the waterplanes, formless on their own, are precise and defined at their horizon. Habitation is simultaneously aligned to these profiled horizons and their inverted densities.

‘Viewing points’, as precise moments, activate view-lines and view-cones, and in so doing acknowledge and celebrate the fundamental symbolic and ecological significance of the regional landforms and their particularities, from the ‘heart of settlement’.

In responding to human presence over time, not merely to the form the city has become, clearly defined, well-managed, humane cities also ensure our wild nature will not disappear.

By Leigh Woolley

1. ‘ Townscape is a word formed on the pattern of landscape. If we speak of landscape we think first of all of a painting. (The artist) sees not only individual objects but the whole together... composing them in such a way as to arrive at an aesthetically valuable whole. The same applies to townscape. Townscape is the whole of urban scenery... made especially so as to create an aesthetically valuable whole.’ N.Pevsner. C20 Picturesque: Architectural Review 115 (1954) p.229

Crucial to human existence, the freedom of outlook and outreach is embodied in island life.

To ‘value a view’ is to acknowledge the intrinsic role of a shared landscape. In response to a city’s location, the characteristics of its landform underpin, and progressively reveal; form, character and identity. All cities are experienced as landscapes, accordingly the way cities are experienced, where they are placed, not just how they are made, demand consideration, analysis and ‘re-view’.

Recognizing that townscape is ‘a word formed on the pattern of landscape’,1 the response engages the latent language of landscape, by grounding and locating disparate parts and layers in the moment of pastiched views. The intention is to offer a ‘frame of reference’ across scales, a ‘re-appearing’ of that which bounds identity in the dwelling region.

Waterplane and landform horizons sustain human presence, and in response, the sense of scale and proportion reinforces and reveals deep prospects, linking near and far, bounding location and urban identity. The margin between land and water confirms a continuous ‘civic’ edge. In being compelled to adapt the space of the city to the terrain, settlement is provided a meandering succession of movements – compelling orientation and re- orientation - revealing extensive and partial prospects and integrating land and its form into the settled world.

Spatially the regional dwelling experience contrasts ‘containment’ by high and rising ground, and ‘release’ across waterplanes. Reciprocally ‘landform horizons’ provide the undulating edge where force accumulates, while the waterplanes, formless on their own, are precise and defined at their horizon. Habitation is simultaneously aligned to these profiled horizons and their inverted densities.

‘Viewing points’, as precise moments, activate view-lines and view-cones, and in so doing acknowledge and celebrate the fundamental symbolic and ecological significance of the regional landforms and their particularities, from the ‘heart of settlement’.

In responding to human presence over time, not merely to the form the city has become, clearly defined, well-managed, humane cities also ensure our wild nature will not disappear.

By Leigh Woolley

1. ‘ Townscape is a word formed on the pattern of landscape. If we speak of landscape we think first of all of a painting. (The artist) sees not only individual objects but the whole together... composing them in such a way as to arrive at an aesthetically valuable whole. The same applies to townscape. Townscape is the whole of urban scenery... made especially so as to create an aesthetically valuable whole.’ N.Pevsner. C20 Picturesque: Architectural Review 115 (1954) p.229