Ricky Maynard: No More Than What You See 1993-2023

For me, documentry photography is a way of life. It represents the historic time we live in. Historic because it is about us and about now. I urge you the viewer of my work not just to look, rather, to see into the pictures and see this world as I show you now.

Ricky Maynard, 1993

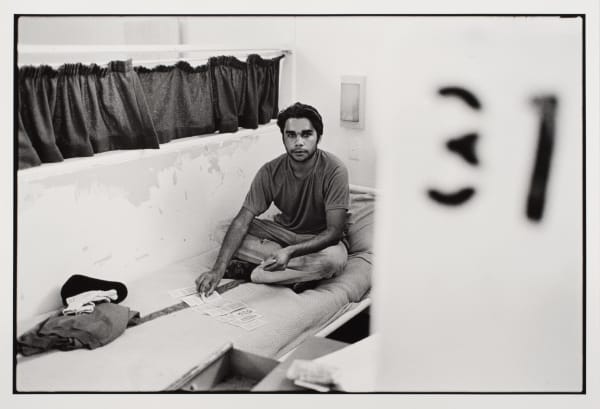

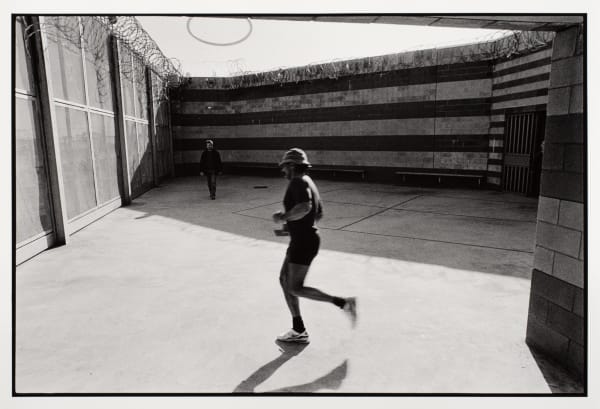

In 1993, the United Nations International Year for the World's Indigenous People, the South Australian Department of Correctional Services presented No More Than What You See, a photographic essay by Ricky Maynard, documenting Aboriginal experiences of imprisonment. The photographs in this collection were taken at Yatala Labour Prison, the Northfield Prison Complex, Port Augusta Prison and the Cadell Training Centre during August and September, 1993.

It was hoped that these photographs would increase public awareness and understanding of the racial issues in the criminal justice system, the implementation of recommendations of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and the complex underlying issues which contribute to the disproportionately high rate of Aboriginal imprisonment.

2023 represents the 30th anniversary of the creation of this seminal series.

Two men, both smoking cigarettes, are separated from Ricky Maynard and his camera by a steel mesh fence that obscures our view of their features. Upon closer inspection, it appears that the men are separated from each other as well. One man is looking at the lens. The other seems to be looking away, though the mesh makes it difficult to tell. Neither man is doing anything else. The only object visible in the background is a grill on the floor.

Maynard took this photograph three decades ago, during the six weeks he spent inside the Yatala and Port Augusta prisons, Adelaide’s women’s prison and the Cadell Training Centre in the Riverland. A practically identical photo might be captured now, despite a major, multi-stage redevelopment that took at least $160 million from South Australia’s already-stretched budget. But today’s equivalent photo would not feature cigarettes. The state’s prisons had all gone smoke-free by 2019 – a health policy decision that seems eminently rational until we ignore the life-shortening effects of oppression and unfreedom. Everywhere, prisoners have reacted to smoking bans with unrest and outrage.

*

No More Than What You See is an ironic title for an exhibition which has always been about much more than can be seen. Born in Launceston in 1953, Maynard had just returned from New York and the tutelage of Mary Ellen Clark to a moment in which the relationship between Settler Australia and First Nations people appeared to be on the cusp of a significant rebalancing.

In April 1991, one of Australia’s longest and most high-profile royal commissions – that into the reasons why so many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were dying in custody – had delivered its five-volume national report. In June 1992, the High Court had at long last found that Australia’s common law recognised a limited form of “native title”, more than 150 years after courts in north America and New Zealand had reached similar conclusions. In December, during an iconic speech at Redfern Park, Paul Keating acknowledged that it was “we” – the settlers – “who did the dispossessing”, who “took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life”: these facts had been denied by settler governments for two centuries. The following year, Keating’s government shepherded the Native Title Act through parliament, and in April, footballer Nicky Winmar made his inspirational and defiant response to spectators’ racist abuse at Victoria Park in Melbourne. It was in August and September of this year, 1993 – declared by the United Nations as the International Year of Indigenous Peoples – that Maynard captured the photographs that would become his first exhibition.

This was also a moment in which First Nations people were taking up the paintbrush and the pen and, in Maynard’s case, getting behind the camera to create works of art, literature, cinema and study, in a country in which they had hitherto mostly been mere subjects for white writers and painters and researchers. If the path had been cleared somewhat by Albert Namatjira, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Jimmy Little and the Papunya Tula Cooperative, First Nations artists remained scarce in Australian cities. But 1993 was also the year Tracey Moffatt’s film Bedevil and Kim Scott’s novel True Country appeared, as well as Marcia Langton’s analysis of the ways in which Aboriginal people watched and made films and TV, in her book “Well, I Heard it on the Radio and I Saw it on the Television”. Her title, of course, is a lyric from “Treaty” by Yothu Yindi, which in 1993 released its third studio album, Freedom, and its first since the double-platinum Tribal Voice.

Maynard is of a generation of First Nations artists and intellectuals who came of age in an era of equal civil rights, following the abandonment of legal discrimination and racist “protection”. Artistic freedom is typically considered secondary to other civic freedoms, but its suppression perpetuates an artificially hegemonic culture in which the unfree appear only in ways that make sense to that culture. Until very recently, Australian Settler culture found it remarkably easy to blame Indigenous people for their own “disadvantages”. Significant sections of it still do. Indigenous people, not the Settler State, were responsible for the rates of child removal and intoxication and criminalisation and imprisonment in their communities. Or so said Settler Australia.

*

Thirty years on, No More Than What You See invites, if anything, even more discussion and reflection than it did initially about the social, historical, cultural and political context beyond Maynard’s images. The royal commission’s report, and the 99 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people whose deaths in police cells and prisons it had investigated, was the event that most motivated Maynard. As he said at the time:

"If you are Aboriginal you are 15 times more likely than a non-Aboriginal to spend time in jail. I felt that it was important for a Koorie photographer to record some aspects of what was happening to our people at this time. After all, the Australian government spent millions of dollars and produced hundreds of pages of reports, but little that Aboriginal people could relate to. It seemed to me that a few strong images had the potential to convey more than all those words."

In 2023, our collective consciousness is different, so we see in different ways. First Nations artists, writers, filmmakers, journalists, researchers – and executives, political leaders and entrepreneurs – are regularly finding their voices, and are speaking Truth to persistent colonial power. Indeed, Australia’s first referendum this century will ask voters whether the Constitution should, a mere 122 years after it was first adopted, recognise First Nations peoples.

And yet, just over three decades after a royal commission made 339 recommendations aimed at reducing the numbers of First Nations people being sent to prison, it is more likely than ever that a First Nations person will be locked up. More than 500 Indigenous people have died in custody since those recommendations were made. Any hope for change with which one might have experienced Maynard’s photographs in 1993 has now likely collapsed into a cynical despair.

Australia’s use of imprisonment has skyrocketed since then. In 1990, for every 100,000 people, 112 of them were in prison. By 2018 that figure had nearly doubled to 221. Indigenous people bore the brunt of that dramatic increase. For every 100,000 First Nations people, nearly 2,500 of them were locked up in 2018. The proportion of all prisoners who identified as Indigenous shot up from 14 per cent in 1990 to just under 30 per cent by 2019.

Even these extraordinary numbers are overshadowed by the biggest story, which has been the sudden and dramatic growth of the Indigenous population in women’s prisons – over the same period that the criminal justice system remobilised to, ostensibly at least, protect women from men’s violence. The very laws, sentencing practices and policing policies which aim to protect women by making it easier to lock up violent men are responsible for imprisoning women – even when they’re victims. This is the very definition of irony, though that seems too glib a word. Speak to a woman in prison, and it’s likely that you’ll be speaking to a survivor of some horrific violence perpetrated by at least one man.

And across the country, First Nations children constitute about half of all kids in detention. In some places, like northern Western Australia and the Northern Territory, that figure is often 100 per cent. The nation was shocked as first Four Corners and then another royal commission exposed the way already-damaged children in Darwin’s Don Dale Youth Detention Centre were being beaten and abused. But the truth is that similar abuses are happening all around the country, as older staff who adopted a pastoral approach have been replaced by a newer, casualised workforce, as detention centres have been redesigned with security rather than children’s developmental needs in mind, and as unethical political leaders from both major parties have shown themselves prepared to sacrifice “bad kids” for populist votes instead of fixing the systems that produce them. We’ve never known more than we do now about the traumatic and tragic lives most criminalised kids have led – which is also to say that we’ve never ignored the evidence about what does and doesn’t work more than we routinely do now.

*

Prisons are the latest expression of the relationship between First Nations and Settler Australians which commenced in 1770 and has never changed its character. From the moment that Captain James Cook fired his musket from the Endeavour between two Dharawal men on the shore at Kurnell, the British invaders – they euphemistically called themselves “settlers” – perpetrated a crime wave of colossal proportions, even according to the law they brought with them from Britain.

The invaders’ law was clear, even in the late eighteenth century: no matter how “nomadic” the “natives” appeared to European eyes, if they occupied land on the Australian continent, they owned it. Yet for the next 150 years, Europeans acted as if they owned it, and resorted to murder and massacre to “disperse” the First Nations. This was absolutely illegal, but colonial and imperial courts endorsed it, settling on the convenient doctrine of terra nullius which allowed authorities to pretend the First Nations had never existed. At the end of this period of undeclared frontier war, which was largely covered up and edited out of settler histories, settler governments commenced policies of “protection” which removed Indigenous peoples’ civil rights. People were forced to work on pastoral runs in slave-like conditions on their own lands. In the twentieth century, settler authorities began removing children. For as many as 13 generations now, settler authorities have heaped trauma upon repeated trauma upon the oldest surviving civilisation on the planet. Now, individuals born into intergenerational trauma are blamed for their brokenness, and locked up. There is little healing in prisons, even less in police cells, and significant numbers of First Nations people die inside them.

It is this phase of the colonial relationship that Maynard documents in No More Than What You See. We see women and men in cages. We see the terrible scars of suicidal despair. We see a heavily-pregnant woman who must be especially daunted by what lays ahead. We see another woman separated from her children, whose smiling faces and birthday wishes adorn the wall behind her, reminding us that incarceration often perpetrates its greatest harms on the most innocent.

*

But Maynard didn’t only document despair. People do survive the prison experience, and Maynard’s subject in 1993 included the many ways in which humanity finds expression within and despite the technology and structures of imprisonment: the steel mesh, the walls, the grills, the barbed wire, the clothing, the simultaneous claustrophobia and agoraphobia. No More Than What You See captures moments of comfort, reflection, art and humour, even between inmates and officers who, while enjoying more agency than prisoners, are also people with limited choices and whose humanity is often conquered by the power they wield and the structures which define their roles.

First Nations have resisted the settler invasion ever since it began. Direct, violent resistance has always been put down in the end, as was Jimmy Governor’s murderous spree in 1900 in reaction to the unrelenting racist gaslighting, ridicule and abuse he, his white wife and their child suffered from their employers near Gilgandra. For its own reasons, Settler Australia now prefers to incorporate Indigenous experience and identity in non-threatening ways, such as the flying of Harold Thomas and Bernard Namok’s flags outside prisons full of Aboriginal men and women. Resistance is futile, especially here, say the prisons. So people resist where they can, even if it’s just to lean against a pole declaring itself ‘Out of Bounds’.

- Russell Marks, lawyer and adjunct research fellow at La Trobe University

Email the gallery to register your interest in this exhibition

-

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 29 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 29 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 14 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 14 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 15 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 15 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 20 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 20 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 8 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 8 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 26 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 26 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 16 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 16 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 23 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 23 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 22 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 22 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 4 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 4 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 1 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 1 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 13 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 13 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 2 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 2 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 3 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 3 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 5 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 5 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series, There are things in this picture you cannot see, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series, There are things in this picture you cannot see, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 13 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 13 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 12 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 12 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 28 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 28 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 9 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 9 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 7 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 7 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 24 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 24 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 10 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 10 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 11 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 11 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 25 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 25 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 17 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 17 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 18 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 18 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 19 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 19 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 21 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 21 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 27 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 27 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 30 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 30 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00 -

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 6 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

Ricky MaynardPrison Series 6 - No More Than What You See, 1993/2023silver gelatin print32.3 x 48.2cm (image size)

40.6 x 50.8cm (paper size)edition of 10 plus 3 artist's proofsAU$ 4,500.00